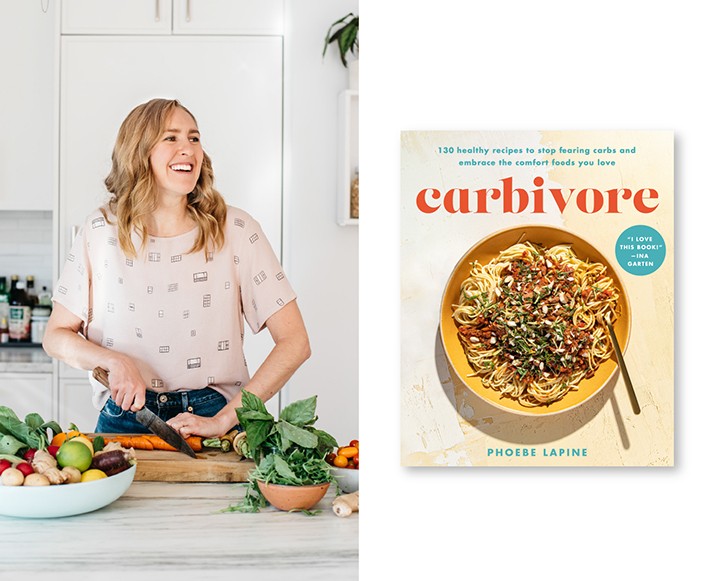

CARBS HAVE GOTTEN A BAD RAP, but cookbook author and gluten-free chef Phoebe Lapine wants us to slow our roll. “Carbs are a convenient scapegoat, but there is more to the story—namely how we eat them.”

While Phoebe suggests that going either high-carb or low-carb doesn’t benefit the average person, she does believe that slowing down the digestion of carbs—and therefore slowing down any blood sugar spikes—has the potential to course-correct metabolic issues that are the cornerstone of so many modern chronic illnesses, including diabetes, fatty liver disease, PCOS, potentially Alzheimer’s, autoimmune disease, and depression.

Her latest cookbook, Carbivore, provides 130 carb-loving recipes that help redefine a healthier relationship with our noodles, grains, and potatoes, so we can have our proverbial cake and eat it too (without the fatigue, insomnia, breakouts, depression, and chronic illness). Every recipe is all about improving your carb tolerance by going Slow Carb, not low-carb.

She gave us some tips on the best ways to go slow carb without sacrifice, so we can get back to putting carbs on the table. All TCM readers can check out Carbivore with 20% off. Use code CARBIVORE through 7/1/24.

5 Ways To Go Slow Carb With Phoebe Lapine

01 | Don’t eat sugar on an empty stomach | The honey in our tea, “fruit juice concentrate” added to dried cranberries, and table sugar sprinkled on oatmeal are all the same things once they hit your body: some combination of glucose, fructose, or sucrose. Whether or not the sources are natural or manufactured in a lab, all types of sugar are energy molecules in their simplest form, and on an empty stomach, can reach your bloodstream as quickly as within 5 minutes of eating them.

This immediacy might be helpful if you were found lost and starving in the wilderness, but since the average American eats 100 pounds of added sugar a year, most of us rarely experience an energy deficit. Part of counteracting the worst effects of simple sugars is making sure you have other macronutrients in the tank to slow their roll to your blood stream.

We can define an empty stomach as not having eaten for 3 hours. Which means it is most important to avoid sweet options for breakfast and as snacks. Sugar on an empty stomach can impact your blood sugar at any time of day, but studies show that they have a particularly negative halo effect in the morning.

Of course, we have been trained, especially in America, to embrace sweet things for breakfast, despite their ingredients being almost identical to baked goods that we’d think of as dessert. But don’t kid yourself: muffins are essentially breakfast cupcakes. Scones are cookies. And sugar-coated cereal with mini marshmallows is no different than candy. Try to rebrand breakfast with delicious options like this savory oatmeal!

02 | Embrace fiber first | If you’ve gotten your relationship with sugar under control, that’s already half the battle. But starch-based carbs like bread, pasta, and rice can also be broken down and absorbed into the blood stream quickly. The most important change you can make falls under the category of “food sequencing.” One study found that you can reduce your overall glucose spike by over 70 percent just by eating fiber first, followed by protein and fat. Starches and sugars (even fruit) should ideally come last (dessert!).

As you learned in my first tip, fiber, protein and fat slow down our digestive organs—specifically our stomach—from emptying its contents quickly into the small intestines. But fiber also plays another important role in the digestive process: it forms a literal barrier as it moves through your system, preventing simple sugars from getting immediately sucked through your intestinal wall into the blood stream.

You can think of your intestinal wall as a fine mesh sieve. If you poured a glass of apple juice through it, the liquid would pass easily and leave no residue. But if you were to add some mashed up apple first? Well, the skins and seeds would clog up the mesh and make any liquid added thereafter take longer to make its way through. The result is a slow drip in the bowl, versus an unobstructed stream.

You’ll find plenty examples of this fiber first, “slow carb” ethos in ancient culinary traditions. In Japanese culture, for example, it’s common to enjoy a bowl of edamame at the beginning of a meal. This means any white rice that follows will be metabolized slower.

03 | Whole foods are always better than processed foods | You can use the above example to understand how apple juice, which has all the fiber removed, hits our bloodstream much faster than a whole apple. The macro lesson is that the closer a food is to how nature intended, the better it usually is for your blood sugar.

An actual whole food is something that hasn’t undergone any processing. It’s the whole almond, not the almond four or the almond milk. Instead of an industrial processor doing all the work, your body will be forced to break down that almond. And this means any carbs will get converted into glucose much slower.

When we chew our food, we break fiber down into smaller particles. But even if you chewed your dinner for 10 minutes straight, you won’t be able to do the job of a high-powered blender, which pulverizes the fibers into microscopic bits. Luckily, I have some other strategies in the Carbivore book for how to fortify your smoothies and soups with whole foods to make them slower carb.

04 | Add a “carb companion” to your meal | When we look back a few generations at our grandparents’ meals, the difference isn’t found necessarily in in what people were eating, but how and how much.

Let’s take toast for example. My great grandparents may have started the day in the exact same way as I do: with a slice of bread. Only instead of slathering it with jam or jelly—or, gasp, margarine—they were more likely to use full-fat butter.

That loaf, if made from white flour, was likely developed from a sourdough starter—a bacterial process that reduces both the gluten and carb content of the loaf. Even more likely, it wasn’t made from white flour at all, but from dark, dense whole grain rye berries.

Instead of orange juice, they might have washed down breakfast with a glass of milk, which arrived in a bottle on their doorstep each morning with a slick of cream on top.

On the surface, the comparison seems like a difference of ingredients and taste. But on a molecular level, the stark contrast boils down to macronutrients. Specially carbohydrates’ other costars: fiber, fat and protein.

If you follow the “fiber-first” mantra and eat a salad before your spaghetti, you won’t have too much to worry about. But as a rule of thumb, it’s best to add fat, fiber, and protein—what I call carb companions—to your bowl.

The good news is that carb companions can make your meals even more delicious! The vast majority of the recipes in Carbivore (and on my website) are designed to have built in carb companions.

05 | Eat More, Snack Less | Even when implementing all these best practices, your blood sugar still rises and falls every time you eat—that is the nature of the beast. Each time we consume food, we ask a lot of our metabolism. During the act of digestion, our immune system is put on hold so that our hormones can rush into formation and blood can flow to our gut to do all the heavy lifting—sorting, secreting, and absorbing.

The solution isn’t to skip meals. Rather, it’s to space out our meals—going 4-to-5 hours between meals so that our organs can catch up. The migrating motor complex (MMC) is our small intestine’s street sweeper wave that cleans up after a meal. When it’s not working as it should, food remnants and (potentially) unwanted bacteria are left to fester in the very long and winding path of our intestinal tract. Our MMC is powered by nerve waves, and they only kick in after a fasting state of 90 minutes or more.

That means if you’re someone who’s prone to snacking, even if it’s a healthy, Carbivore-approved whole food snack like a handful of nuts every hour, your MMC isn’t able to fully clean up after your meal. This can contribute to bigger issues like SIBO, but it can also make your overall digestive system less efficient.

If you’re feeding yourself nutritious, well-balanced meals—meaning plates packed with carb companions, and free of hidden sugars on a regular schedule—you shouldn’t be facing the types of food cravings that drive snacking.

Lastly, most pre-packaged snacks are full of added sugar. Often, these will make it even less likely that you’ll get to the next meal without going back for more snacks.